LISTLESS: Good Burgers

we love burgers, so we wrote about them

[Emily]: In May 2022, I earned my Reiki III certification, making me a Reiki Master, and by earned, I mean I paid a couple hundred dollars to sit in an Italian woman’s basement and learn how to draw Japanese symbols that I would then trace with my fingers in the air above recipients after they reached a state of deep relaxation, and in doing so, open blocked channels of energy, which I’d sensed through hovering my palms over, or lightly touching, their bodies.

This is one of those ymmv situations—how do you feel about one more white person co-opting an Asian philosophy and practice? How much will you buy into this idea that I have the ability to move energy throughout someone’s body? How much will you buy into the idea that people even have energy coursing through their bodies? It’s a hard sell unless you’re already kind of into this stuff. But, I will say this. Has someone ever touched you very gently? Has that comforted you? If not, can you imagine being lightly touched while you relax deeply in a sleep mask listening to New Age flute music? Still not into it? Hmm. Okay. Ever hear of this guy?

He was also into doing this sort of thing. I’m not Jesus, no, but what I’m saying is the practice of comforting, healing touch has its roots in many places, and if you don’t like to be touched in this way, it’s maybe because you’ve never been touched in this way, which is also maybe why you should be, and why this works, even when its validity is constantly questioned (it’s a pseudoscience….or “quackery,” if you will). Anyway, this isn’t about me trying to touch you. This is actually about cheeseburgers.

During Reiki III, while we sat in silence on hard-backed chairs, while our Master was putting the Dai Ko Myo into our heads and blessing us with Holy Water brought back from the Vatican, I had a vision. I’d just had the best meditation experience of my life, so maybe I was more open to receiving ideas. But in this vision, I saw a soft brown cow, and it came up to me and let me pet its face. And in real life, while I sat with my eyes closed waiting to be attuned, I wept. What I understood this to mean was that I should never eat meat again. Immediately after, when we were all mingling before practicing our skills, I thought, people are going to think I’m fucking insane. Not there, in that room—those people would be like, oh yeah, of course. Nice vision. But elsewhere?

I began Reiki because my high school teacher and friend suggested I learn it after my father died. It had been a comfort to her after losing her husband, and comfort is all I wanted in my grief, since the way I had been dealing with it was to drink my way through a Costco bottle of Maker’s Mark. I’d already assumed I would be different after the classes, different in some intangible way. But we had also been warned that Reiki attunement might fuck with our vibration tolerance, which meant we might not want to eat dead animals anymore. And since that day I haven’t, besides fish maybe once a week, which I’m planning to cut but keep not cutting because it makes having Portuguese in-laws easier, plus it keeps open the possibility I might once again participate in the Feast of the Seven Fishes (a long shot, since most of my Italian relatives are dead, but perhaps that’s why I yearn so badly to consume fried smelts while people argue around a large table).

Luckily there are really good fake meat options now. The fake hot dog landscape is still abysmal, but the pink sludge that you can turn into a crisped-up burger is pretty damn good. They didn’t have that during all the other times in my life I attempted to become vegetarian1. And I’m sure better people might look down on me for even wanting a “fake cheeseburger” option at all. I shouldn’t be eating something that’s masquerading as a killed and cooked living being. But honestly, I’m not sure I’d be as committed if I wasn’t able to have a reasonable facsimile of a cheeseburger. They’re too important to me.

And they’re important to me most likely because I ate so many as a kid. I watch a lot of old commercials (my hobby) and recently saw a McDonald’s spot2 that showed a common marketing angle: “we are there for you no matter what the occasion.” Depression, celebration, tooth loss—McDonald’s! That’s how it was for us growing up, only the occasions were just like, because it was Friday, or because my mom had three kids to feed, or because we were sick of fishsticks.

We’re talking burgers for this LISTLESS because summer (peak burger time) is ending, and also because Molly and I both don’t eat beef, but burgers are our favorite. I want to dig a little into why—I think it’s got something to do with its role as a comfort food (did you know that the first modern usage of that term was by Liza Minnelli, and that she was talking about a burger?) and I think it’s also got something to do with all the really great instances of burgers in our favorite media, media that, in many ways, has been itself comforting to us. Meta-comfort, if you will. Is the burger comforting the character? Is seeing the burger or its consumption comforting the viewer? Is the media itself the comfort? Have I written myself into a corner? Let’s see!

I sometimes think of this moment my dad had at Mr. Wok, our favorite Chinese buffet. He brought us frequently, despite one of us getting violently ill almost every time we went (I’m talking like, during dinner, one of us would be stuck in the bathroom…never him, though). He’d go for two things: some nights they’d have crab legs, and he and my other sister would go nuts eating those crab legs, and then sometimes they’d have these little steamed cheeseburgers that we’d all devour. He found out the secret from a waitress once, which was that they buttered the buns before they wrapped them up in wax paper and lined them in the tray. Good burger memory, but the Mr. Wok memory I mean to bring up is actually him telling us about when he was there with his friends, the ones who helped him put on his cable access show and occasionally screen old movies, the aptly named Cinema Boys. I remember him saying that he was watching this one Cinema Boy eat the crab legs, and that he just couldn’t stop watching him do it, that he was mesmerized. Everything looked so good because of the way he was eating it3. Many of my picks here have to do with that—the manner in which the burger is consumed, not necessarily the burger itself.

But the burger itself is still important; several of my foundational burger texts seem to be a type of burger. Take for instance those favored by the burger king of the Popeye universe, J. Wellington Wimpy. May we all one day have a Wikipedia entry like this:

Wimpy is a soft-spoken romantic, intelligent and educated, a lazy coward, a miser, and a glutton. He is a scam artist, and frequently bereft of either cash or lodging (due to both his lethargy and voracious appetite), but frequently feigns high social status (sporadically, and possibly inaccurately, referring to himself as a former college alumnus). Besides mooching hamburgers, he also picks up discarded cigars. Popeye often tries to reform Wimpy's character, but Wimpy never reforms.

Wimpy’s burgers have been stuck in my mind forever, these flat, disc-like things, sometimes a little ripply at the edges. Sloppy-joe-esque, but neat. They are plain, no-nonsense hamburgs. The type of burger you can eat hundreds of and never get full. The type of burger I always envisioned while doing those childhood math problems where they’d give you a menu and make you calculate an order, and burgers cost, like $1.10. Juice was like 15¢. Milk was 10¢. This is my food ASMR, the imagining of a simple, old-timey burger you pay for with coins, not the triple western bacon burger mukbangs of today. There’s something innocent, something wholesome about Wimpy’s burgers. I’m reminded of gentle afternoons watching Mr. Rogers order a cheese sandwich from a restaurant. (He pays a dollar eighty-seven. NO TIP.)

This type of burger also exists in non-cartoon form, and my top example is from Beethoven’s 2nd, a fun little family film that also features an attempted rape. Charles Grodin and Beethoven enter (maybe against their will?) an eating contest where you partner with your dog, and they decimate a bowl of plain, flat burgers.

As Molly and I wonder to each other how blurry the line between ASMR and fetish is, I realize that although that’s something I’d never think I was into, Grodin eating those burgers…well, I’m not sure anymore.

But back to animation, since there are many great cartoon burgers, and cartoons are also a major source of comfort. When researching the significance of comfort foods, scientists divided them into four categories, and one was “nostalgic.” This is how cartoons function for many of us as well. Like, I had a bad cold last month and could do nothing more than watch Rocko’s Modern Life on my couch; when my dad was in hospice, I stayed up rewatching Harvey Birdman episodes every night; I love a weed seltzer/Ren & Stimpy session after a long day. Much like with McDonald’s, I barely need an excuse to marathon animation, but the greatest cartoon comfort for me is The Simpsons.

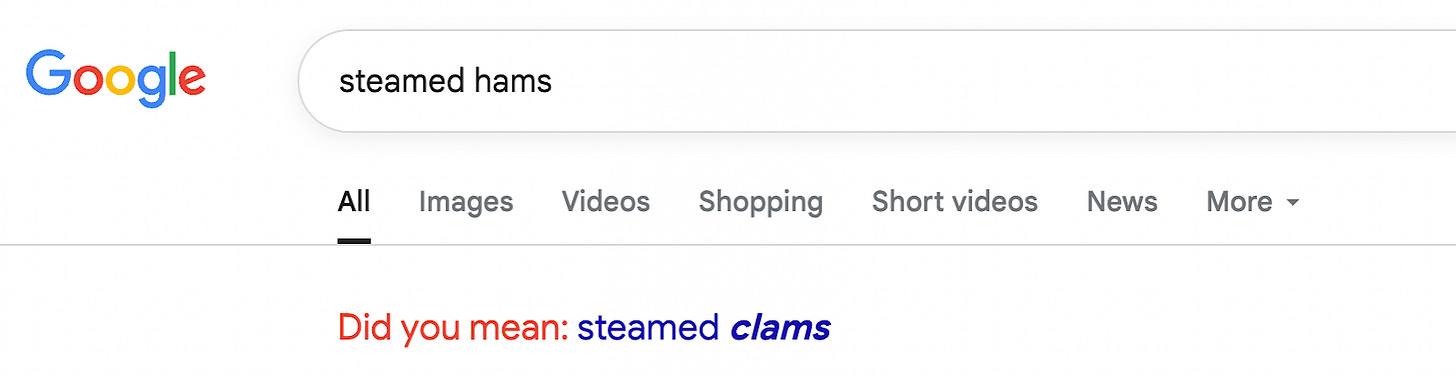

There was a glorious time in the late 90s/early 00s when you could watch The Simpsons in syndication for a solid two-hour block by switching between two local Fox affiliates, and it’s this daily ritual that allowed me to commit so much of those episodes to my memory. We watched whatever one was on, even if it was repeated on the other station an hour later. And we LIKED it. Anyway, what can I say about steamed hams? There’s even an ASMR aspect to it, Chalmers’s little chomp-chew, although Homer’s perfected cartoon eating sounds.

There’s also a burger scene in the (sort of) first episode4 of Doug, a show that lies somewhere in the realm of gentle nostalgia comfort for me, but upon a recent viewing, there’s overlap into someplace…else.

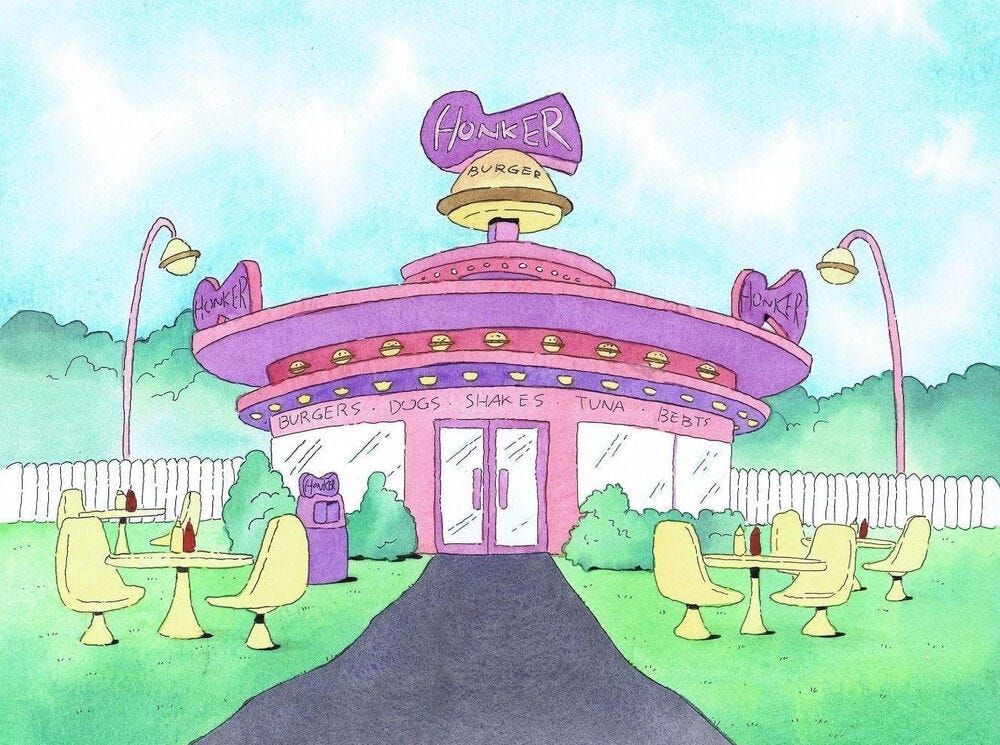

Doug moves to Bluffington and is immediately tasked with getting his hungry family some food, only he doesn’t know where to go. Mr. Dink wrangles him into watching a welcome movie that mentions the Honker Burger. Bluffington is a strange place for many reasons, but I’d say one of the main ones is the town’s interest in honking. Is this a kind of language? A vocal stim or tic? I’m not sure. Whatever the case, Skeeter Valentine must translate Doug’s order, and the two become fast friends. Doug sees Patti Mayonnaise and in his love-trance, slips on a ketchup packet, setting up his tangle with Roger and the whole “bag a neematoad” plot.

But we finish the episode back at the Honker Burger, where Doug’s dumb ass slips on a ketchup packet again, only this time, the ketchup squirts onto Patti’s open burger. Doug has a breakdown under the table, but she reassures him it’s okay. I’ve been doing some research and introspection on the fanfic concept of “hurt/comfort” (i.e. asking my friend to explain it to me, then wondering if I’m into it) and I think this is that. To be clear, I am not into these two cartoon characters having this highly sexualized (watch it back…very odd…unexpected squirting, open buns, embarrassed apology) moment, but I am curious what seeing this moment did to my brain.

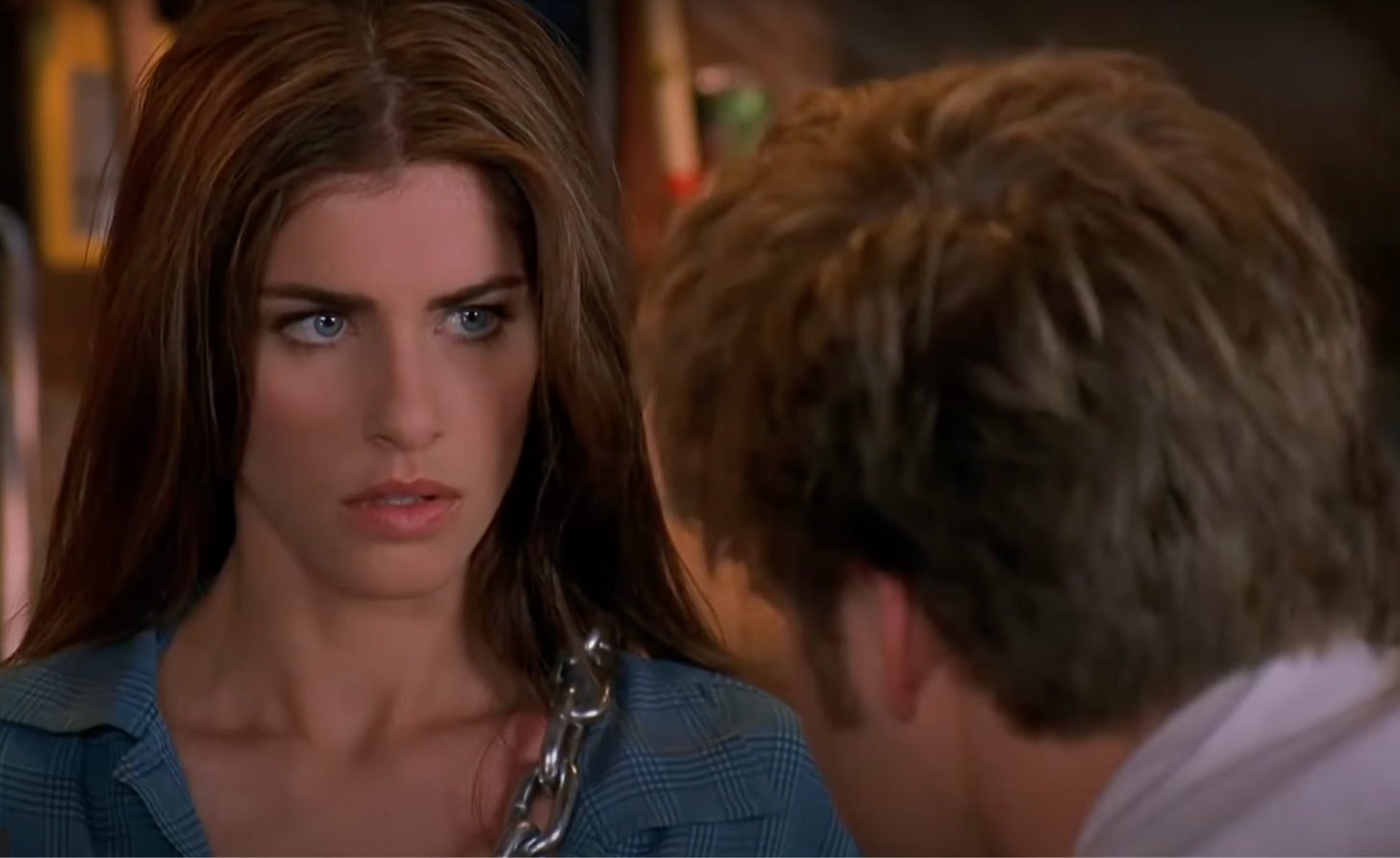

Did it, perhaps, prepare me for the sexual awakening I’d have later on in life while watching Saving Silverman? It’s not exactly hurt/comfort, and it’s not exactly a burger either (although at the end of the clip, Jack Black refuses to answer the door because he’s eating one), but it’s close enough. Mustache-d Steve Zahn getting Amanda Peet a Big Montana from Arby’s and feeding it to her while she’s chained up combines pretty much everything I’ve mentioned already. Peet plays Jason Biggs’s controlling fiancée, and Zahn and Black have kidnapped her to keep Biggs safe/get him back to his true love before she takes her final vows to become a nun. This movie rules.

Although the Zahn/Peet interaction is a ploy to steal his keys, they do get married at the end after beating the shit out of each other. This tension adds dimension to this earlier scene. Here especially, it’s not the burger itself but the method of eating that matters most. And there’s comfort there, in a few ways. Zahn brings Peet her requested meal. He has a thing for her, but he has to keep up appearances, saying, “I just happened to be by an Arby’s and they were throwing out some old food.” Then he feeds it to her.

The eating is woven seamlessly into the sexual tension. I won’t get too deep into food fetishes, or hot girls eating big burgers5, but it’s worth meditating on for a second. Like, what is it about the burger that can also veer into the sexual realm? The mess? Opening your mouth so wide? And why so many burgers and not hot dogs—too obvious?

In all of these scenes, the burger is a character’s comfort food in that it is a vehicle to fulfill some need or lack, whether that’s extreme and insatiable hunger, romantic or sexual connection, or the desire to be liked by your superintendent. The burger contains multitudes. And for the viewer, watching the character eat the burger can be the comfort, too, because it looks good, or it creates an ASMR tingle, or more than a tingle, or maybe somewhere in the Venn diagram overlap of all of that.

Comfort also comes from familiarity, which is a large part of the burger’s appeal. A McDonald’s hamburger is going to taste like a McDonald’s hamburger no matter where in the world you get it. And many of us have media that functions similarly: comfort movies, comfort shows, the media you seek out like an old friend. It’s like the cartoons I’m always playing. I know what’s going to happen. No surprises. But it’s a warm blanket on a hard day. It’s someone’s hands hovering over your body. And one of my favorite comfort watches is also the best burger movie ever made.

I really believe Good Burger holds up. Stacked cast, actually funny, quotable, A+ soundtrack, and a dance scene I hope to write about in a future LISTLESS. What is Kurt’s backstory? Where are Ed’s parents? It doesn’t matter. This is a live-action cartoon universe. I don’t want to talk about Dan Schneider6 in any positive light, but given the choice of every show on whatever stupid amount of streaming platforms we must subscribe to, my kid frequently gravitates towards Schneider creations, their non-sequitur weirdness. Plus they’ve often got actual plots and actual kids. Good Burger has that same absurdity, which is why he’s always down to watch it with me.

I realized when I logged my latest viewing that I’ve watched Good Burger every summer for the past three years, and pre-Letterboxd logs, I found twitter proof that I’d done it. None of that was premeditated—as the temperatures rise toward scorching, I guess viewing becomes a reflex. A yearning for the summer of 1997, most likely.

I was about to turn ten. My summer life revolved around finding cool bugs with neighborhood kids, eating deli grinders, renting tapes from my dad’s video store, tearing through my summer reading list on the living room couch (the only room with air-conditioning), and watching hours of Nickelodeon, on and off, from morning until either Nick at Nite or SNICK began.

In the mid-90s, Nick was doing some wonderful stuff. I talk about it so frequently here because not only did it help shape me creatively, but I’ve seen my 8-year-old’s programming choices: pretty much complete dogshit. I don’t think this is a case of misguided nostalgia, of me being “old man yells at cloud” about it all. I firmly believe there’s a lack of respect towards kids in this world in many ways, but especially regarding their media consumption. For all the talk of gentle parenting and screentime reduction, there seems to be a failure in really viewing children’s entertainment as a worthwhile venture7 at all anymore, when it can be used in truly excellent, enriching (non-corny) ways. We need Nick News. More kid-centered game shows. More live-action kid shows in general, things with a narrative (there are a couple shows you can find if you dig through various streaming services, but who can afford every fucking streaming service? Another annoying part of this whole problem). We need care and depth in their entertainment, a slowing down, not brightly colored computer-orb characters or cop dogs or anthropomorphic vehicles screaming at us in between jumpscare commercials. Everything looks the same. Sorry!

Anyway, I went to the Paley Archive in NYC earlier this summer, and I watched this compilation of Short Films for Short People, which were films made by kids for kids, many of which are considered lost, as well as a selection of other interstitial short films Nick used to play. Their creativity, their variety—as well as, again, the idea that many of them were made by kids—was so moving to me. I felt the buzz of seeing something I hadn’t seen in so long, of an old part of my brain lighting up, but I also felt a heavy sadness.

But of course we don’t want to feel that sadness, the mourning necessary when becoming an adult, that grief accompanying change. We want comfort. And everyone marketing to us knows that. So, besides not creating new and worthwhile media for children, they’ve been pumping out a lot of garbage that seems largely directed at millennial parents, people like me, people not sure how to grapple with the shitty world we’re living in, the world we’ve (perhaps stupidly) brought children into, so we cling to cutesy microgenerational names, frying our eyeballs on an endless loop of nostalgic Reels, or TikToks reposted as Reels, or some Buzzfeed-quiz-personified acting out greenscreened skits, telling us what genre of alternative music fucking Chuckie Finster would listen to, and all of this is to say I regret to inform you that Good Burger 2 sucks.

But you already knew that, right? Assumed it? Maybe hoped it wouldn’t, but knew deep down it had to? It capitalizes on these feelings of comfort and nostalgia, delivering a film so soulless it made me momentarily question my love for the original. So it’s been a comfort to me, going back to that 1997 world, but I know I can’t live there. Sometimes I try, I really do, but I also know this:

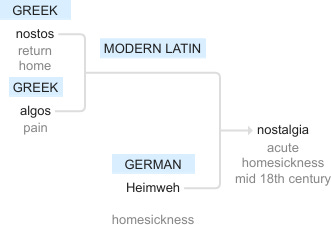

Part of nostalgia is the pain (it’s right there in the etymology), but it’s the part the nostalgic person wants to ignore, or cover up with whatever comfort reminiscing might give.

When I do Reiki, there’s usually an emotional swell at the end, a kind of release. Sadness moving through, maybe. This is the really important part, letting this sadness out.

My kid got sad the other day because he was remembering these bedtime stories his dad made up for him a few years ago. He started crying because he said it was so nice what his dad did, but it made him sad, too. And he couldn’t understand why it was making him sad. We talked about it, and part of it was this self-awareness of growing up, about how he no longer asks for those bedtime stories. I hugged him and let him cry, and I talked about having two feelings at once, and about nostalgia as best as I could. I even showed him the etymology chart. I said I used to miss my mom all the time, even when she was right next to me. It didn’t make any sense then, and I couldn’t really explain it now, but I understood him, and it was good he was telling me his feelings. My impulse, though, wasn’t to say all of this. It was to say hey, you wanna get McDonald’s?

*

[Molly] There’s this line that Andy says in the last episode of The Office: “I wish there was a way to know you're in the good old days before you've actually left them.” When I first heard this, it got stuck in my brain. A new obsessive thought. I now think about it every day. Not the exact words Andy says, but the sentiment of it. I’ve found myself deeply preoccupied with this idea of recognizing how good I have it right now, in this very moment, because the future will certainly be worse. And the only things I’ll have to sustain me are the memories of better times.

You’d think then that I’d have a lust for life, an appreciation for all that is around me, and that I’m only ever living in the moment.

But no, it’s just another thing to worry about. I feel a constant pressure to enjoy what’s happening because I know it will never be like this again. I feel a constant pressure to store away each detail, no matter how negligible. Each smell, each sight, each person. What I’m wearing, what the weather’s like, how much everyone means to me. Because this moment is fleeting and will soon only be a memory that I may or may not be able to conjure up at varying degrees of clarity.

Even when things are bad, I know I’ll look back on them someday with a sick kind of yearning. So even then, I’m trying my hardest to absorb the minutiae of my surroundings.

Of course, in doing all of this, I not only pervert the memories I’m trying so hard to create, but the moments themselves, and the whole thing is pretty much for naught.

I believe this is probably all tied to the fear of forgetting. Something I worry about quite often is dementia setting in early. And I’m near-positive this will happen. (My grandmother had dementia. And dementia is sort of hereditary. And I look just like my grandmother did when she was younger. So it’s just a matter of time before I’m unable to remember things, too.) Because of this, I take pictures of unimportant things that may be important to me in the future. I write things down that are seemingly meaningless. I feel an urge to keep things that I know belong in the garbage.

As much as I wish I could, I know I cannot archive every instance in my life. It’s not feasible, and it would be exhausting to do so. But it is such a scary thought that we can never go back. Even with diaries and pictures and ephemera from the past, we can’t ever be there. It’s always going to be too blurry.

Luckily, we have burgers.

I think the closest thing we have to a time machine is the burger. And the clearest your past will ever be to you is when you’re eating one.

I posit that most of us have a core burger memory: one specific instance of eating a burger as a child that was so significant that it imprinted itself onto your memory folds. And anytime you’ve eaten a burger since, a part of your brain lights up and makes a connection to that root memory. Whether you are aware of this core burger memory or not, I think, depends on how deeply you think about burgers. If you’re doing a lot of burger meditation, at most, when you eat one now, you will conjure the memory itself, feel every feeling associated with it. And if you’re not that introspective about the whole thing, at least, you may get a subtle, unconscious pang of comfort and nostalgia, not fully sure why. Only that you’re suddenly reminded of better days and a time before you were uninhibited by your adult brain. Before you knew about calories, high cholesterol, and slaughterhouses.

Despite currently being a vegetarian, cheeseburgers have long been my favorite food. So of course I have already discovered my core burger memory. In it, I’m little, maybe eight. I’m watching the Kids’ Choice Awards on my family’s wooden box TV. I’m by myself. My mom is upstairs, dad’s at work. My sisters are out with their friends. I’m eating a cheeseburger from Burger King. And that’s it. I don’t remember what year it was, who was hosting the ceremony on TV, or what my Big Kids Meal toy was. Only the taste of the burger, the subtle burn on my tongue from the excessive amount of mustard, and the feeling I had. I’m alone in this memory, but not sad. My body and mind are at rest. In a sort of stasis. No anxiety, completely relaxed. Nobody’s there to judge me. I’m not thinking about school or homework. I’m just myself, and I’m free.

When I eat a burger now, I’m in that at most space. I’m not just getting that unconscious pang of comfort. I’m getting every feeling associated with my root memory.

One of those feelings is, oddly enough, a sense of belonging. The fact that it was a Burger King cheeseburger and the Kids’ Choice Awards were on is important. This is probably the complete wrong thing to admit to, but I find a deep, deep comfort in giving in to capitalism (not all the time obviously, but in brief, sporadic bursts). Riding the corporate wave, sitting back and letting other people decide what I like so I can take a break from thinking my own thoughts. Because not thinking is bliss sometimes. And I really like that feeling.

It is the whole point of the system we live in, right? Let us (corporations) think for you so you give us all your money. In my defense, I was, like so many others, inundated with consumerist propaganda as a child. Happy Meal toy movie tie-ins, title songs for huge Hollywood blockbusters playing incessantly on the radio, Ninja Turtles popsicles at the ice cream truck, collecting Pokémon cards and Beanie Babies. MTV. Spice Girls. Coca Cola. American Idol. Liking things that everyone likes. (These things were popular for a reason, right?)

In writing this newsletter, I’ve discovered the thing I’ve always wanted most is belonging and acceptance. Surrendering to blatant consumerism gives me that. It may be a synthetic belonging and a corporate acceptance, but it feels like I’m part of something. And that feeling brings me joy. A very real feeling. In the back of my mind, I know there’s something artificial about it. But it’s okay, because I like the artificial feeling, too. It’s like drinking a Slurpee.

(No doubt that Emily has already mentioned Good Burger, a film with a pretty strong anti-corporation message. Now, I’m not saying I’m on Mondo Burger’s side or anything. I’m just saying, if it were a real place, I would have eaten there a lot. I’m a sucker for good branding.)

Clearly burgers mean a lot to me and, I assume, they mean a lot to others as well. So when I see a burger in a film, I clock it. I’m hyperfocused on it. Why did the filmmaker choose a burger for this scene? Why not spaghetti and meatballs or a rotisserie chicken? Because a burger is never just a burger. If we all have these core burger memories—the one thing in common between them being a sense of comfort—burgers in film are symbolic.

Let’s take Stand by Me for instance, a movie overflowing with symbolism. Four boys learn that a local kid was hit and killed by a train, so they follow the tracks in search of his body. The train, the tracks, the deer in the famous deer scene (that I just partly watched and had to shut off because I started weeping) all stand for something deeper. But I think the burgers in this movie do too, and they are often overlooked.

Early in their journey, the boys realize they didn’t pack anything to eat. Gordie (Wil Wheaton) loses the coin toss, so he’s the one who has to go to the corner store to buy food. Earlier that year, Gordie’s brother Denny died in a Jeep accident. Any time he’s by himself, you can see how hard the death has hit him, how deeply it has affected him. His heart is broken, and the only time he feels better is when he’s with his best friends. They are his greatest comfort and a welcome distraction from bad thoughts. Without them there at the store with him, his thoughts no doubt turn to his brother. And he feels lousy.

He wants to feel better; whether he’s aware of it or not, whether it’s at the forefront of his brain or buried deep in the caverns of his mind, Gordie knows burgers will help. Because what’s more comforting than having burgers with your friends?

He’s in the middle of buying some “hamburg,” when the owner of the store starts pestering him with these questions and comments about Denny.

And now Gordie’s being reminded of these better times when his brother was still alive. He has a flashback to when he complimented a story he wrote.

His grief is compounded. And with it, I’m sure, his yearning for burgers. Of course he chooses hamburger meat, a pack of buns, and four Cokes. They will remind him of the better days. Before his brother was killed, before he became “the invisible boy” to his parents, before he felt completely hopeless and lost.

In 28 Days Later, after Jim (Cillian Murphy) wakes up from a coma in the middle of a zombie8 apocalypse, he’s looking for hope and comfort, just like Gordie. When he and the group of survivors he hooks up with stops at a grocery store, we get an A.M. 180-set shopping montage. Selena grabs Terry's Chocolate Oranges, Frank some malt liquor. We don’t exactly see what Jim picks, but we can hear him in the background asking about buns.

Even though “bun” could mean something else in England, it seems Jim’s got burgers on the brain. In the very next scene, they stop at an abandoned restaurant to siphon gas from a truck. Jim sees a sign: LAST CHEESEBURGERS FOR SIXTY MILES. Despite the fact that they just stocked up on food, and despite the fact that realistically, he knows he will not find burgers inside, he feels a pull towards it.

Inside, the restaurant floor is littered with corpses, including a baby’s. An infected child jumps out and tries to attack Jim, but he does what he has to and kills him. It’s not insignificant that Jim’s first kill is a kid, since symbolically, he must first kill his own innocence in order to survive.

He emerges from the restaurant, his childlike hope for burgers gone. Reality set in.

In the opening sequence of Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, the leader of the Explosive Ordnance Disposal team, Staff Sergeant Matthew Thompson (Guy Pearce) and his two squadmates (Anthony Mackie and Brian Geraghty) attempt to destroy an IED in Iraq. However, a wheel falls off of their little wagon carrying the charges. So Thompson has to enter into the blast radius and bring the charges to the IED himself.

While Mackie and Geraghty’s characters help him into his bomb suit, Thompson tells the others his plans for the IED, then pauses. “Craving a burger. Is that strange?” he says.

I think there are two things going on here. Number one. Thompson is scared. Consciously, he’s craving a burger, but subconsciously, he’s craving better times. He wants to be comforted and safe and home, not away from his family and friends risking his life disarming bombs. (No doubt the burger is also a symbol for America here but I’m not getting into that.)

Number two. Thompson doesn’t know how to communicate to his squadmates that he’s scared. Again, he’s probably not 100% conscious of what he’s feeling or why he’s saying this burger line. But Bigelow is. Her whole deal is masculinity. She9 knows a cocky U.S. Army Team Leader would not openly admit to such a vulnerable emotion.

The whole thing is reified when they show Thompson’s face once he’s all suited up. Self-assured Thompson, mid-laughing and joking with his squadmates, for one split second, looks panicked. You see the fear wash over him. Of course he fucking wants a burger.

I understand that if I’m talking about core burger memories, I may need to mention The Menu at some point. I don’t quite remember why Ralph Fiennes makes a cheeseburger for Anya Taylor-Joy at the end of this. I’m not going to rewatch it because something about it didn’t exactly work for me. I think it may be the fact that there’s a beautiful montage where Fiennes’s character makes the most mouth-watering cheeseburger you’ve ever seen and then Taylor-Joy takes this bite:

Dear filmmaker, do another take!

If you don’t understand what I mean, please zoom into the picture. It’s giving:

But anyway, there’s a line in The Menu where Fiennes’s character says, “I’ll make you feel like you’re eating the first cheeseburger you ever ate. The cheap one your parents could barely afford.” And that’s really, in essence, what a core burger memory is.

But what about the other burgers in film? The ones that don’t quite fit into this category? Because the way they’re presented to us, they couldn’t possibly mean comfort or nostalgia or hope for better times. These “other” burgers are greasy, messy. Or sometimes the complete opposite: dry-looking with stale buns, like they might hurt on the way down. They’re available to you at late-night fast food restaurants and 24-hour diners. At truck stops and seedy motels. You eat them during after-hours stakeouts in the seedy underbelly of a city. In between puffs of unfiltered cigarettes. You hear the buzzing of the neon restaurant sign above you as its light reflects off of your sweat-drenched skin. These are night burgers.

These burgers don’t connect to my core burger memory or your core burger memory, but instead to a collective and primordial one. An imprint left over from caveman days. A longing, an urge, a hunger. Our id. Our innate desire for meat.

With night burgers, our darkest desires emerge. We’re ravenous and feral. We know about the calories, the cholesterol, and the slaughterhouses. We just don’t care.

Night burgers have long been represented in film. Let’s look at the way Kenickie eats a burger in the diner scene from Grease. The waitress delivers the food to the table. “Grab it and growl,” she says. Then comes his famous, “A hickey from Kenickie's like a Hallmark card” line, punctuated by him tearing into a burger, devouring it like a predator would prey.

It wasn’t even Kenickie’s burger to begin with. He does what he wants, when he wants.

John Carpenter flips the whole idea of I guess what I’ll call “day” burgers on its head in Christine. Though it takes place in the ‘70s, the entire movie is a hey-look-at-how-stupid-the-‘50s-were kind of thing. He totally warps the meaning of some of the decade’s mainstays. A burger at a drive-in, for instance–normally a symbol of teenagedom, nostalgia, fun times, etc.–is instead used as a weapon.

At the drive-in, Arnie, Christine’s owner, accuses his girlfriend Leigh of being jealous of Christine. Leigh subsequently “hits” Christine. When Leigh takes a bite of her burger, the killer car’s radio flicks on, and “We Belong Together” by Robert & Johnny blasts through the speakers. This startles Leigh, causing her to choke on her burger.

In a lot of ways, The Driller Killer is a spiritual sister to Taxi Driver. Reno (Abel Ferrara), an artist who’s hoping to get enough money for rent by selling the giant portrait of a buffalo he’s painting, loses his mind. A punk band, The Roosters, incessantly holds band practice in a nearby apartment while Reno tries to work. Here is a man who would not take it anymore…

The movie is grimy, ‘70s, and takes place in New York, but Reno is not Travis Bickle. He does not do things like try to protect and save 12-year-old Jodie Foster. Instead, he begins killing men experiencing homelessness with an electric drill that he plugs into a little portable battery pack. As Reno falls deeper into madness, he becomes the embodiment of our most primal desires. Filled with hate and rage one night after The Roosters perform in the club he’s patronizing, Reno takes to the streets, drill in hand. What follows is a visceral montage—set to a Roosters song—of Reno killing, inter-spliced with footage of the characters back at the club. Tony Coca-Cola (The Roosters frontman) singing, people dancing. Back to Reno. He’s doing a little dance himself over a dead body. Or is he twitching?

After The Roosters song ends, the killing spree is far from over, and he drills several more men, ending the night with a comically long drill-to-forehead session with his final victim, but not before giving the dead man a small peck on the side of his forehead—the side that’s not covered in blood.

The very next scene, Reno opens his refrigerator. He’s worked up quite an appetite (though, to be fair, I’m not 100% certain this is the same night, but I don’t think it matters). The fridge is sparse. An open beer can, a leftover McDonald’s sandwich (contents, at first, unknown to the viewer), and a carton of milk.

He goes for the beer first, chugging it as it drips down the corners of his mouth and onto his chest, no doubt causing his exposed chest hair to mat. Next, the McDonald’s. He opens the styrofoam box. It’s a Big Mac. He inspects it, picks at it. There seems to be a very tiny bite taken out of it. Maybe from his girlfriend who lives with him or from his girlfriend’s girlfriend who also lives with him. He palms the burger with one hand and shoves it into his mouth.

Without having swallowed yet, he grabs the milk. Drinks it straight out of the carton. It, too, drips all over. Unfortunately, his binge is interrupted by Tony Coca-Cola. The two talk, but we never see Reno even wipe his face.

Two scenes later is the famous pizza scene where Reno uncontrollably eats almost an entire pizza as if he hasn’t seen food in days. Many say this is the most disgusting scene in the film. I disagree. It makes me want a pizza.

Why do we need two of these scenes? Does one act as preparation for the next? Or is their purpose to show just how insatiable Reno is? I don’t know, but I’m glad we got them.

In After Hours, Griffin Dunne’s Paul needs a place to hide out while being chased by an angry mob. It’s the middle of the night. What’s even open? He finds reprieve in a diner and heads to the restroom. But the owner stops him. He tells Paul that he must order something first, and so Paul promises he will order when he’s finished. He requests a medium rare burger paired with a coffee. Acid city. My stomach hurts just thinking about it. Then, under the guise of feeding the meter, Paul bails.

Several scenes later, Paul unwittingly ends up back at the same diner. The owner emerges, and with a real fuck-you attitude, serves him the burger and coffee.

I could go on. There are so many of these movies. ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s run-all-night type movies. They’ll have a diner scene. Someone’s scarfing down a burger. Putting their cigarette out in it. They’re probably also wearing dirty jeans.

Night burgers continued past the ‘90s though. Don’t worry.

In Take Me (2017), Ray (Pat Healy) kidnaps people for a living to help them with their various addictions and problems. In the opening, we see him abduct an overeater who lies about having a salad for lunch. As punishment, or a form of negative reinforcement, Ray abducts him, ties him up in his basement, and forcefeeds him 13 fast food cheeseburgers.

I must mention Spongebob once more. Because one of the best night burgers ever is from “Nasty Patty,” the episode where Spongebob and Mr. Krabs think they committed murder. It’s dark as hell, and it weaponizes the Krabby Patty, the usual omnipresent force of joy and purity throughout the series.

In “Nasty Patty,” a criminal is on the loose pretending to be a health inspector in order to obtain free food. So when a health inspector comes to The Krusty Krab, Mr. Krabs convinces Spongebob that he’s an imposter, and that they need to give him a tainted Krabby Patty as payback. They do foul things to the burger: drop it in the toilet, put toenail clippings in it, douse it with hot sauce and sea horse radish–”the gnarliest stuff in the ocean.”

When they serve it to the health inspector, a bug flies down his throat. He chokes and hits his head on the table. Krabs and Spongebob are convinced he died, and that their burger caused it.

When they find out the man they just supposedly murdered was actually a real health inspector, they decide to bury his body over near Shallow Grave Road.

They’re interrupted, however, by some classic incompetent cops and end up putting the “corpse” in the back of the police car that then, cops at the helm, gives them a ride back to the restaurant.

Spongebob drags the body behind the restaurant as the normally non-lighted Krusty Krab sign, now a slime green neon light, flickers overhead.

The health inspector, of course, turns out to be alive, but it doesn’t exactly detract from the fact that you now know what Mr. Krabs and Spongebob are capable of. It’s ghoulish.

I must confess, I stopped writing this on SEVEN separate occasions because I needed to go order a burger10. That’s the power of the core burger memory. It calls to us. With each burger I ate, I was transported back. Back to when I was eight and calm and free. Or, hell, maybe I went back further. Because I didn’t even use a napkin.

*

I have failed at least three times because the McRib came back

This makes me think of Lucas Mann’s great essay on Brad Pitt eating, and Michael Wheaton’s response essay. Both do a great job of trying to understand the appeal of these Brad Pitt eating supercuts while also reflecting back their “own shit”

There are more Doug burger things I can talk about, but I can’t remember them all, and they’ve taken it off the streaming service I used to watch it on. Now there’s only the fake and shitty Disney version available. So instead, here’s a Youtube video I found called “DOUG HONKER BURGER AMBIENCE 38 MINUTES EXPANDED”

Although I must point out is he’s in Better Off Dead, another important entry in the burger canon

Okay, yes, maybe because it’s too expensive to do so, sure. I know PBS is in trouble, I know educational venues are drowned out by child influencers held at gunpoint by their parents as they unwrap blindbags or fake-prank each other. This is a deep and complicated problem, and I don’t claim to understand it all or have a solution (except to like, play Pete & Pete for my kid and hope for the best, or complain in newsletters)

Technically humans infected with the rage virus; related: in Zombieland (2009), the cause of the zombie apocalypse is a contaminated burger

And Mark Boal

Impossible Whopper

Spread this out over the past week, delight after delight after delight !