LISTLESS: Prom Special!

taking some risks, all while using as many footnotes as possible and not really talking about prom

[Emily] Molly and I went to a high school play last month. The kids wrote it themselves, and it was based around their actual, real punk band. The band played songs as palate cleansers between each slice-of-teenage-life vignette. I don’t know what the singer was saying or if the guitar was working because the drums were so loud, but hell yeah to the whole thing. Hell yeah to high school punk bands, hell yeah to those high school punk bands being from cities that are always described as “failing.” Hell yeah to writing and creating your own art. But hell yeah, most especially, to the realization I had midway through the play: holy fucking shit am I glad to not be in high school.

That might sound a little weird coming from me, who is seemingly obsessed with high school, but let me explain. While I’m drawn to teenage life as a subject matter in my writing (and my EMDR sessions), I do not wish to actually return to it, to be in that body, which I realize more and more I fucking hated, ever again. And the reason I likely keep returning to it as a subject matter is because, like a ghost, I have some kind of unfinished business there. I’m writing towards something, trying to figure something out. This was confirmed when I started writing this newsletter— which I thought would be a fun one! May! Prom Month! (also notably Mental Health Awareness Month, ha ha ha!)—and it took twice as long as it normally does.

I think about my progression through adolescence, particularly from ages eleven to fourteen, a lot. How weeks felt like years, how I was all raw nerve without nuance. Every word, glance, or song left an indelible impression on me, the aftershocks of which I’m still able to feel deeply today. I’m mostly grateful for that. I often think of this quote from one of my favorite quoters, Stephan Jenkins (the guy from Third Eye Blind):

I’ll go back and play some old song, and it puts me back in the mindset of a time, but also gives me this perspective of time. I feel more deeply connected to the totality of my life than many people do because of that—actually living in the emotional state of your biography.

Writing creative nonfiction allows me to do that, to “live in the emotional state of [my] biography,” and I welcome that dissection and discovery, even when it’s hard. And this time it’s hard.

I divide my adolescence in half. The first half is what I mentioned above, that eleven to fourteen timeframe. Maybe I read The Catcher in the Rye too much, but as a teenager, I was extremely aware of the concept of loss of innocence. And I was aware of my own loss not right as it was happening, but soon after. I think I had to do that to distance myself from a rash of bad things at the time. To make it a story.

What contributed to my loss of innocence? Although I can likely trace this back to a bunch of close family members dying in my childhood, or my exposure to pornography, or my dad’s infidelity, or when he pointed out in front of an entire dressing room that I grew boobs, I more often associate it now with my realization that “I must use this body that I hate and am uncomfortable with in order to get boys to like me because otherwise they do not see me,” which has largely resulted in me now, in my thirties, questioning my own gender and what the fuck went so wrong. And what went so wrong? This, starting at fourteen: losing my virginity, performing sex acts in front of people, my OCD and depression getting infinitely worse, an uptick in abuse that led to an assault, a couple other things I can’t bring myself to name yet, and a suicide attempt. So, that’s why I hate high school.

Anyway, that’s a brief history of me, a lot of which I’ve written about in some capacity before, but some I haven’t. I’m not going to be too vague about it here because in order for the rest of this newsletter to have any deeper meaning, you have to know that stuff. Every early draft of this was too vague, and every early draft of this sucked, and maybe this draft does, too, but at least I’m taking the risk.

I only went to my senior prom. I wore the stupidest dress with the dumbest hair and had a pretty bad time. We drove there in his old Jeep, but the rest of our friends, including my younger sister (not Molly), hung out on a party bus. And when we arrived at the Aqua Turf, the same banquet place my parents (who would finally divorce later that year) had their wedding reception, things didn’t improve. I was embarrassed to dance, the food was gross, and I’d already had sex. Why did I even go?

Well, I went because some lingering part of me had high hopes. And I’d had high hopes for two reasons:

Middle school dances provided some of the most meaningful moments of my early adolescent life (again, ages eleven to fourteen).

I watched a lot of movies and TV shows.

It’s important to note that I was watching all of those high-school-centered movies and TV shows before high school, i.e. points 1 & 2 were happening simultaneously. In what I (and probably any other kid raised by TV at the turn of the century) was watching, the school dance always served as the climactic event, a moment when everything could shift dramatically. Cinderella shit. And by 2005, my senior year, I needed a win.

I’d been primed even earlier, through sitcoms and music videos and even a couple Are You Afraid of the Dark? episodes (duh), but then in middle school I really found teen movie paradise. I’d rent them, or simply rot on the couch at the mercy of cable, fantasizing about my potential. What will I do? Who will I be?

Also priming my brain for the Big Show (prom), were those middle school dances. Our city had like ten Catholic grammar schools, and usually about once a month, one of them would host a dance in a church basement. You could buy sodas and candy and little glowsticks. You could request “Forgot About Dre” or “Will 2K” and they’d maybe play it or “The Bum Bum Song” and they definitely wouldn’t play it. You could pine after the most beautiful perfect boy you were in love with but who, even though he talked to you every night on the phone for hours, was in love with your best friend. You could wait on the side, hoping he’d ask you to dance, and sometimes he would. You could silently judge cheerleaders. You could wear non-uniform clothes, including large jeans. You could watch grind trains until some parent chaperone got wind of it. You could see mysterious kids from other schools and become obsessed with them, maybe even exchanging phone numbers or screennames (such as with an unfamiliar boy named James who kind of looked like Reese from Malcolm in the Middle). You could do, I mean to say, pretty much anything your little pubescent brain could conjure up. The idea was hope, here. The idea was yearning.

That yearning, combined with the constant stream of movie bullshit I consumed, had letdown written all over it. Expectation—specific, fantastical expectation—leads to disappointment. Did you know, like…have you ever heard that, uh…life is not like a movie?

For this LISTLESS, after many failed attempts at trying to organize every school dance trope1 within various media only to arrive again at the LISTLESS goal (ahem...to be list-LESS), I’d like to zoom out a bit and talk about that piece of it, because it’s the piece that’s affected me the most: the school dance as life-changer.

I’ve written about Angus before in an essay for wig-wag magazine2, but I’m gonna do it again, sorry. It’s just that good, and it was something I watched on cable all the time. In Angus, the titular character is an outcast bullied for his weight, dreaming for a shot with the girl he’s in love with, Melissa Lefevre. We’ve got other crucial teen movie elements, like The Bet/Prank, The Sidekick, James Van Der Beek as a great stock jock bully, etc., but if I can peel all of that away for a moment, what left its mark on me the first time I saw this movie, and what can still make me weep, is the dance itself. The dreamy underwater feeling. The way she guides him. The way he keeps his eyes shut tight—from fear, from concentration, from disbelief, maybe. That repeated cut to his face turning toward the spotlight. And, my god, Mazzy Star.

Sometimes with these teen movie characters, their level of hopeful inexperience borders on excruciating, and they become unpalatably annoying3 because of a hyperfocus (usually about “getting” a girl), but for Angus, even when he’s obsessed with wanting Melissa to like him, there’s this other piece present, this audacity and grittiness to his character, this sense of survival. His “I’m still here, asshole!” speech is an all-timer for me, whether that’s because I saw the movie at the exact right time in my life, or because I understand it more now: there’s really no promise that things will get better, but you should continue anyway, because you have inherent worth, absent from the values others put on you. And if you stay, if you survive, you get to keep trying.

Another scene that can make me weep, sometimes even if I just think about it, is the dance scene from the pilot episode of Freaks and Geeks. Activities I took part in during 2000-2001 included going on this website, cutting out tiny pictures of James Franco from magazines, signing online petitions to bring the show back from cancellation, and watching episodes I taped off of Fox Family. It’s weird talking about it now because it’s so well-known and spawned such mega talent, but when it was on, it was hard to track down (hence its lack of viewers and eventual cancellation). I had to work to see the episodes, even in the Fox Family run, and whatever I taped certainly wasn’t in order, but I know I’ve seen the pilot the most. The texture of the show—the way it looks, the details—is something so special. They’re always setting shit in the ’90s & ’00s now and “iPhone face” aside, it rarely feels authentic (PEN15 did a great job, although I have a bone to pick with whoever included a Livestrong bracelet in Gabe’s wardrobe), but Freaks and Geeks still doesn’t feel like it came out in 1999.

The pilot episode is perfect. It sets up every character in the way a pilot must, but they already feel fully-formed. They feel real. We understand the tension within Lindsay almost immediately, and even though the stuff with Eli (or rather Ben Foster’s portrayal) might be viewed differently now, it’s still so painful to see that struggle, of trying to do the right thing but still getting it wrong.

I think we’re all overcome with emotion by a Youtube comment from time to time, but thank you Dave Keefe for this description of the Homecoming scene in the pilot:

Full disclosure I have been trying to type up descriptions of the scene and I keep crying so my eyes blur and then I can’t see what I’m typing, like…Jesus Christ, Sam walking into that dance alone? You should probably just go watch it. The scene, the episode, the whole series.

Something that really hit me hard during this viewing is Lindsay watching Sam, her sudden smile, her joy. How his abandon becomes the catalyst for her own dancing. I love that Sam takes risks, that he asks Cindy at all, and beyond that, that he leans into the tempo change4 after only momentarily freaking out. I love that the labels blur all the time between groups and identities on this show (Daniel as Carlos the Dwarf? come ON) because from an adult perspective, it’s so authentic. Everything feels so black and white at the time, but looking back, it is sort of blurry. That’s because this is the age when we really start to figure out who we are. Sometimes we got it wrong, sure, but sometimes it expanded our entire world.

PEN15 also has a pretty perfect dance episode. In “Dance,” the finale of the first season, the girls are in a fight, so we have tension from the start. But we still get the lead-up to the event itself, which includes the distorted nightmare of both girls shaving their legs for the first time (in a scene rivaled only by the growing tampon). They take pictures in perfect millennium-casual outfits, pedal pushers and butterfly clips. Anna licking her fingers to slickly separate her two face-framing tendrils captures the disgusting, spot-on details of this show, while Maya’s dance with her kind-of-mutual crush, Sam, gets about as close to conjuring my personal adolescent ache (the experience of having a boy friend but not a boyfriend, know what I mean?) as anything I’ve seen onscreen. The sweet, awkward scene starts when Sam is dancing with his girlfriend. He keeps looking over at Maya5 but denying he’s doing so, until finally he approaches her. When they eventually decide to dance, Sam shares a secret that ruins the moment, and Maya flees.

Anna also experiences complete humiliation—a brutal “no” from her crush6—and the girls turn to each other. The tension instantly dissolves, and so does everyone in the room, as they perform a surreal routine to Des’ree’s “You Gotta Be.” It’s reminiscent of another one of my favorites, Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion. Both contain post-heartbreak epiphanies of friendship, which bloom into really great, weird interpretive dances, which solidify the idea that being yourself is the only solution to the pain.

Romy and Michele actually has two important dance scenes (or more, if you count the longer club scene). First, in a prom flashback, Billy Christianson tricks Romy by saying he’ll dance with her, but then he secretly zooms away with his girlfriend on his motorcycle. The girls wait among the deflating balloons. When it’s clear that Billy’s gone, Michele says, “I’ll dance with you, Romy.”

Like the PEN15 episode, the tension of the movie also comes from a sudden rift in friendship, but humiliation brings the best friends together once again. What’s important in that repair is the commitment to authenticity; the humiliation and failure happens when the characters try to be different, when they refuse to acknowledge the reality of themselves. In the big reunion dance scene, the girls are joined by fellow redeemed loser, Sandy Frink (Alan Cumming). And the popular kids get what’s coming to them at the end. It’s a lovely dance revenge fantasy7 without pig’s blood.

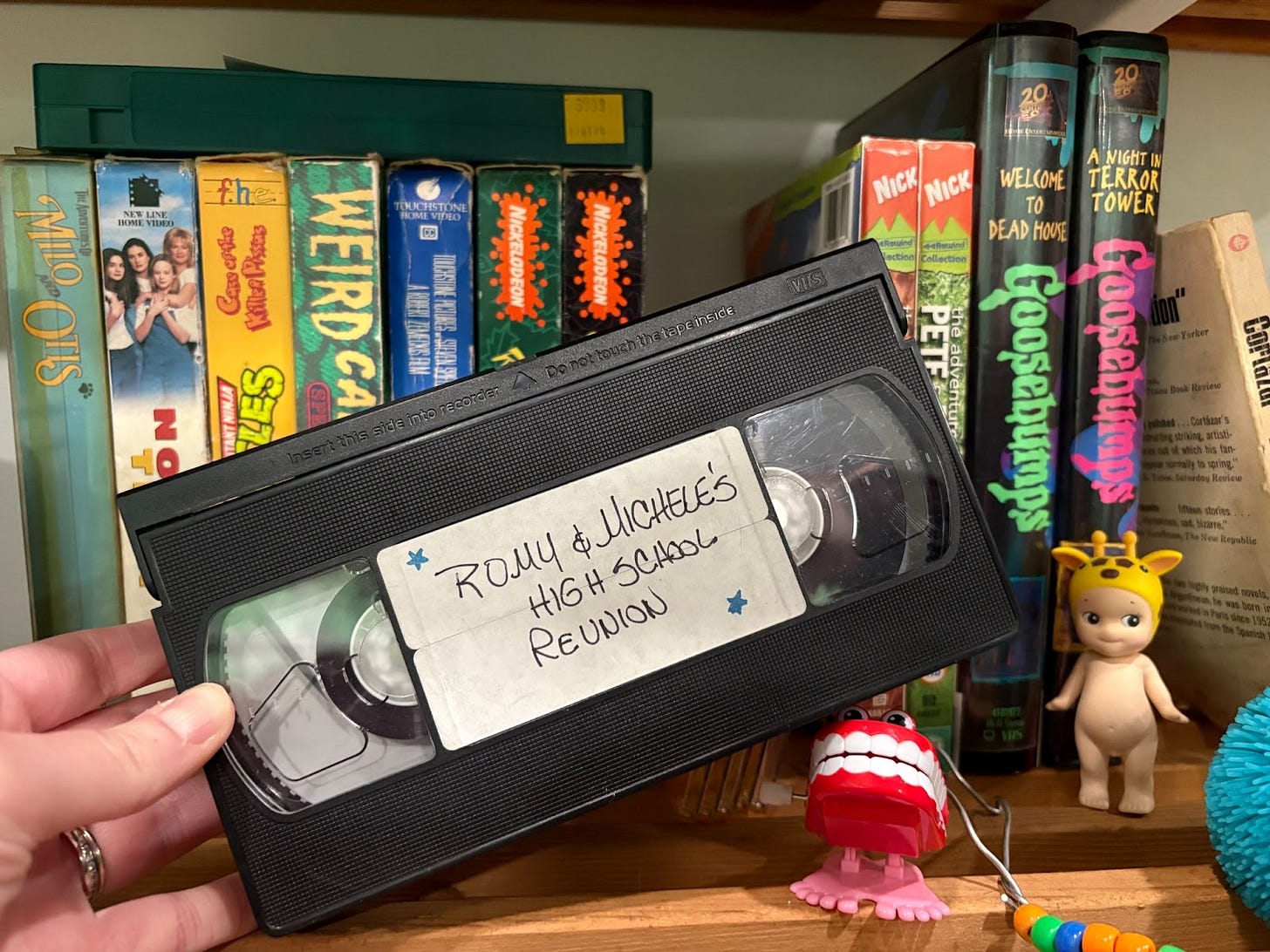

My sister, the one who went on the prom party bus with my friends, one of the cheerleaders on the cover of my book (a popular girl, is what I’m saying), gave me a pin a few years back that said “I’ll dance with you, Romy.” She gave Molly one, too. The two of them dressed as Romy and Michele for Halloween in 2000. We don’t have any pictures of them in the costumes my mom made because Molly decided not to go through with it, but we still have the dresses. This movie was one of our household staples, and we’d watch the taped copy my dad made us all the time. Lines are seared into my brain, and we’d quote it constantly. We would even do the Ramon scene, where Romy is pretending to have loud, passionate sex with a man in exchange for his car, and no one told us to stop? Like, we did it a lot.

So that’s why I’m going to ignore any more critical dissections of this movie (along with my own footnote) and look only to the dance scene itself. I don’t need the context of the whole movie to know what it represents to me, a kind of return to childhood. Even though it’s not part of the (some would say *too*) long dream sequence, it feels dreamlike. Like a memory, like something unreal. The naïveté of the girls is there in how silly the dance is. In their bare feet. It’s what came to mind when I watched the dance scene from the 2012 adaptation of The Perks of Being a Wallflower: it’s a living room routine.

That movie was released the month I turned 25, but I’d been imagining an adaptation8 since middle school, when the book first came out. I can’t tell you how many times I read that thing. I brought it everywhere. I’m reading it right now, in fact, because I just watched the movie again for this newsletter, and it was slightly disappointing, so I’m trying to see if I’ve been completely wrong about the whole thing.

I saw the movie in theaters with Molly and my good high school friend. I hadn’t been so in touch with my past self back then, not like how I am now, so seeing those moments onscreen made me delirious and nostalgic. But now, since I’m sort of always delirious and nostalgic, I can be a bit more critical, specifically to say that Emma Watson’s performance kind of ruins the whole thing for me. BUT let’s just look at the homecoming scene. In the book, it’s not really that explicit. In the movie, it’s crucial.

Logan Lerman is the right guy for the role, and his discomfort as he leans against the wall at the dance is so quietly devastating. While he watches Patrick and Sam dance to “Come On Eileen,” you can see the choice flash across his brain. He’s at a precipice. He can choose to remain there, observing, or he can risk rejection and participate. And he risks it. He takes the long walk over to join them, and they not only welcome him, but they make it easy for him to participate; Patrick lassoes him with his scarf and they become a trio. They absorb him into their group.

Molly and I both have social anxiety. For me, it often manifests in moments like this, where I have a choice to lean into fun, but a type of fun that will make me vulnerable to criticism about my physical body. Will I join this group of friends singing along to the radio? Will I dance with acquaintances at a writing retreat? The choice flashes across my brain, my heart pounding. But my body locks up. My voice gets caught. I see that in Lerman’s Charlie, and can feel the vicarious relief when he’s accepted.

All of these dance scenes have “life changer” moments, but they’re also examples of characters risking rejection or discomfort in order to become the most authentic versions of themselves.

There’s still some deep wound in me I’m uncovering. A lot of the repair work I’m doing is trying to untangle parts of my gender and sexual identity that got pretty warped when I was this age. And yeah, May was prom month and mental health awareness month, but June is pride. So, maybe this is working out how it’s supposed to.

I’ve been immersing myself in the past for years, and now I’m understanding it as an attempt at healing. I’m looking for clues. I go back to scenes like these and dig around—into the scenes themselves, but also into the version of me I was when I first watched them, or read them, or thought deeply about them. I can see that person so clearly. I can feel those daydreams again: what will I do? who will I be? And this time, I won’t lose that thread of discovery. I’ll try something different. I’ll take the risk.

*

[[[secret little link to a slow dance playlist as a reward for reading this far]]]

*

[Molly] Growing up, I had loads of trouble picking out clothes at the store. I did everything I could to avoid attention already, and I didn’t want that to be ruined by a particularly puffy sleeve or busy pattern. I did not want the t-shirts with the big glitter sayings. Just one light reflecting off of a sparkle on a DRAMA QUEEN ANGEL STAR PRINCESS SPOILED CUTIE t-shirt and it’d be like a giant LOOK AT ME OVER HERE sign. It’d also be a dead giveaway that I was immature, childish, girly–even though I was, in fact, quite obviously and objectively an immature little girl. But, more than anything, kid me wanted respect. (Why? I’ve yet to figure out. Probably something to do with my yearning to belong and some ingrained misogyny that I’ll never be able to shake off.) And respect, to me, was considerably more possible to obtain wearing no-frill clothing. But, finding these types of garments proved difficult. Every option presented to me was loud. I have this memory of being overwhelmed in the little girl clothing section of Sears. It was like the saturation was turned up. Bright colors and leopard print and everything was so shiny. And all the t-shirts, those fitted ones, were cut with a faux waist, a girl cut tee or whatever they're called. I’m 8, what do I need that for? My body goes straight up and down.

I think about the little girls like me, the girls who wanted to blend in, who wanted to be taken seriously. Where could they shop? Wasn’t there anything for us? Where was the Limited Too normcore section?

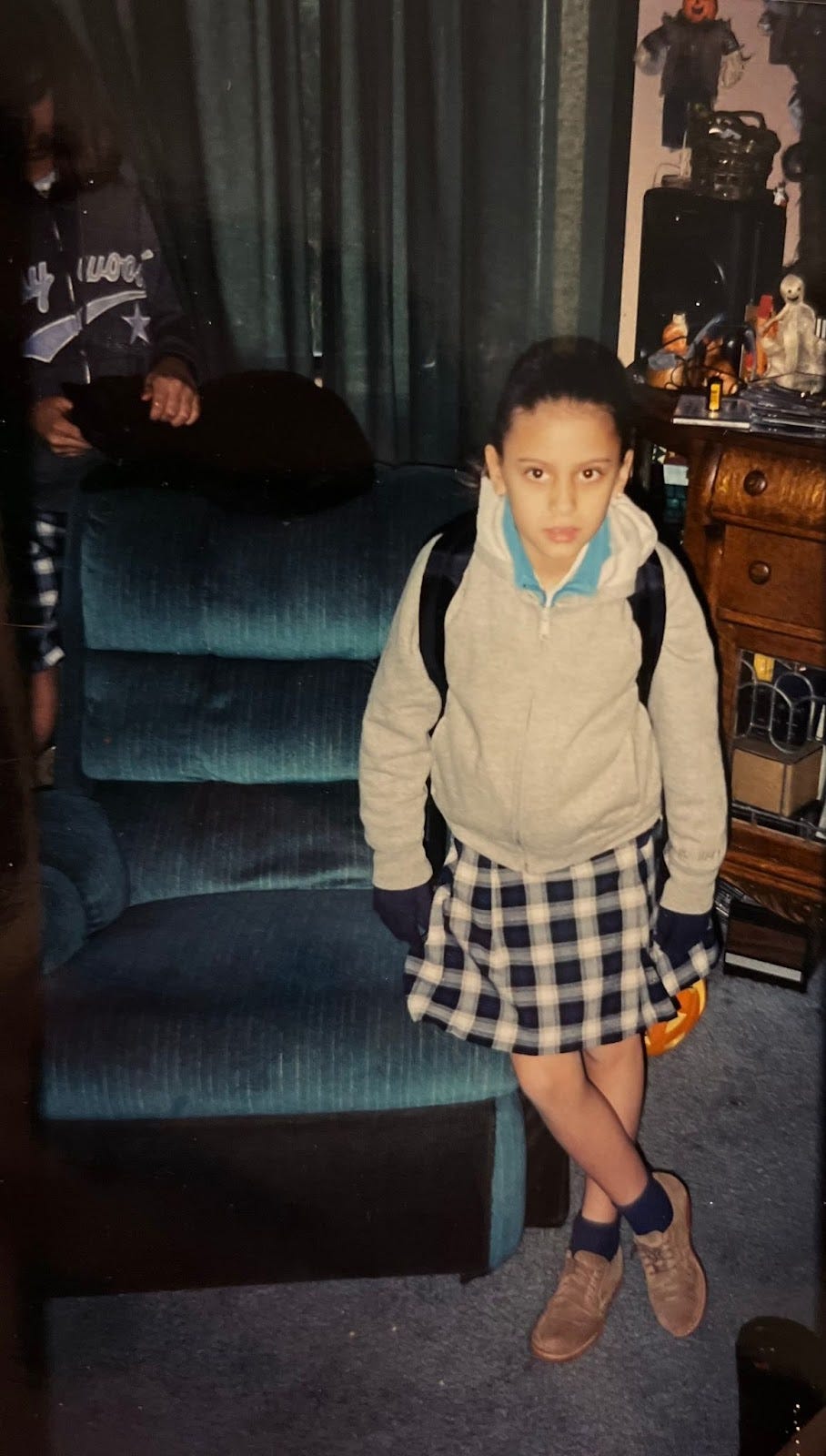

It was a big relief to me that from kindergarten to 8th grade, I wore a uniform every school day. A Catholic school uniform. Plaid skirt, white button-up, sweater vest, and tights in the fall and winter. Long pleated shorts and white polo in the spring and summer. Everyone wore a variation of this. Some added their own small touches: headbands, knee socks, crude hems on their skirts (rolling them created a lump). I didn’t mess with anything too much. My friend Claire rallied for the girls to wear long pants like the boys did. I stayed away from pants so I would not stick out.

Every year, the school had spirit week. In first grade, for crazy hat day, this girl Tori glued Spice Girl dolls to a white satin top hat, and I think she won. Oh yeah, these were contests. I don’t really remember anything else of note about these contests until seventh grade. For crazy sock day that year, I wore sparkly pink knee socks, something that was miles outside of my comfort zone. But, ultimately, not too crazy. Normal enough, I thought. I didn’t want to win the contest. I just wanted to wear sparkly pink knee socks because they were pretty and I liked them. And I thought you were supposed to wear crazy socks on crazy sock day.

Later, in the parking lot, which was also where we had recess, Cody G. approached me, looked down. “Nice socks,” he said, as he put his hand up to his mouth to stifle a laugh. He didn’t have crazy socks on.

This two-second incident became a defining moment for me. Whatever desire I had before to blend into the crowd was amplified so loud that it would affect me for the rest of my life. From crazy sock day on, I no longer participated in casual days: random Fridays where, if you paid $1, you could wear your own clothes. I did not want to be an easy target. Cody, however, paid the dollar, wore big jeans like it didn’t matter.

The next year, my friend was having a sleepover. It was different, though, because a few of the popular girls were coming. I felt myself panicking because I wore crappy pajama bottoms and my mom’s oversized t-shirts to bed. What would they say? “Nice PJs.” I acquired a brand new matching set of pajamas, like the girls on The Disney Channel wore. Satiny collared long-sleeve button-up top and matching bottoms. They sold them like this, so nobody could possibly say anything to me. When it was time to get ready for bed, everyone changed into their ratty old sweats and oversized t-shirts. I came out looking like a cartoon or an old-timey Scrooge or something. (I didn’t have a nightcap on but I may as well have.) Nobody did say anything to me. They didn’t have to. I was saying enough in my head for the both of us.

I lost either way. No effort and I missed out on fun, normal kid things. Too much effort and I missed out on fun, normal kid things. I decided the first one was less painful. Best to just not participate. For years, I continued this lifestyle. No bright colors, no ripped jeans, no makeup, no short hair. Just normal. Normal. Normal.

The worst was that Halloween, the best day of the year and one of the only reasons for living, got harder and harder. So, senior year, when all my friends wore their costumes to school on the one day out of our four years of high school we got to be out of dress code, I wore a navy blue polo shirt, khakis, and a zip-up hoodie as if it was just another day. The only seniors in regular clothes: my religious friend who didn’t celebrate Halloween and me.

Senior year was also PROM. Finally, the topic of this LISTLESS. All of this to say, when The Big Dance came around, there was no way I was going to let my classmates see my choice of dress or shoe or hairstyle. I pictured myself at prom. I didn’t even have a dress on. Instead I was a skinless body, uncovered muscles, ligaments, and veins pulsating, red and raw, a trail of goo behind me. Leave myself exposed like that? No way. Sure, I had to deal with a few teachers telling me I’d regret not going. My grandmother said something too. But I could take it. Nothing would have compared to someone verbally Carrie-ing me. I had to protect myself. Everyone left early from school that day to get ready. I sat alone for the first few classes until finally I left out the side door and walked to my friend’s house. The religious one. I braided her hair into an updo. More kids came over to take pictures in the backyard, and I wondered if they felt embarrassed or if they thought they looked good. Maybe both. I was handed digital cameras and snapped group shots of my glammed-up friends until my mom picked me up. I got in the car. She said, “You didn’t tell me it was prom.” I have no memory of what I did that night instead, but I can say with 100% certainty, I didn’t get made fun of. At least not to my face.

Since I skipped prom, for LISTLESS: Prom Special, I’ve decided to share a list of films that's been in my head for over a decade. These movies disrupt the whole notion of prom, dismantle it, break down each stupid little tradition until there’s nothing left but crushed paper cups and shriveled streamers crumpled up on the sticky fruit punch gymnasium floor.

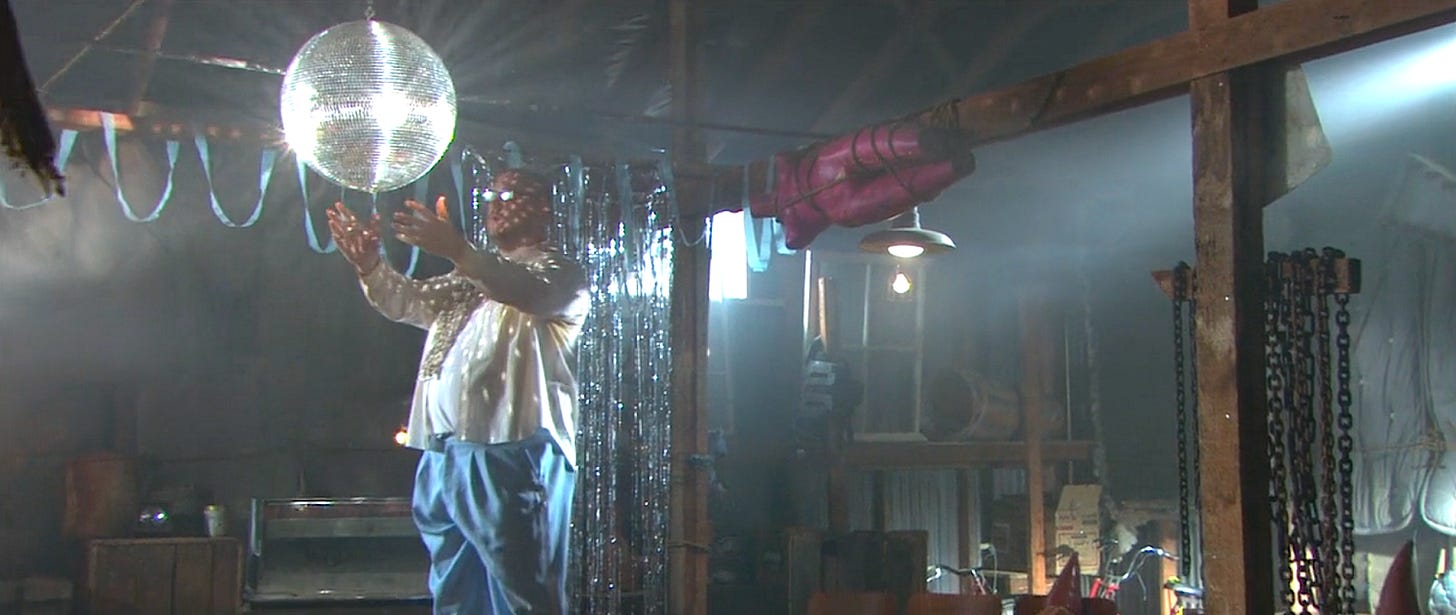

This isn’t just a list of like, prom-themed horror movies though. It’s more a branch that hangs off of that genre tree. Like, Carrie’s the trunk, Prom Night and Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II are on one side, and these movies are new growth on the other side. These movies all go together in my head. They all have a similar look to them. They are slick. Colorful. Shiny. (Yes, Carrie is shiny but also blurry, like maybe you have astigmatism.) And they are all from a specific time period. They are 2008/2009. And when I think of them, I see the glint off of a bloodied disco ball. At a later date, Cabin Fever 2: Spring Fever could potentially join this list as it seems to fit most of the criteria. However, I don’t remember a single thing about it except, of course, that one of Emily’s underrator picks (Giuseppe Andrews) reprises his role from the first film as party cop. I know I saw it, but I guess it made no impact on me whatsoever. And I’m not rewatching it because it looks gross.

First up is Dance of the Dead, a 2008 low-budget horror comedy. It’s prom night and toxic sludge from the local power plant is reanimating corpses. A random assortment of teenage stereotypes (a screw-up, his type-A girlfriend, three members of the sci-fi club, their bully, a couple of cool guys in a band, and a dateless cheerleader) band together to defend the town from zombies as they make their way to the school to warn their prom-going classmates of the inevitable.

When they finally make it to the dance though, they find that almost everyone there has already turned, but the prom is still raging. All the teenage zombies are still doing typical teens-at-a-dance things: playing music, taking photos, spiking the punch (albeit with blood), just slower and like, gruntier.

If horror movies not only reflect our collective anxieties, but show us certain unfavorable aspects of our society made to oppress us, Dance of the Dead dissects tradition. Stupid, pointless societal conventions. Conformity. Heteronormativity. Expectations. And it “scares” us by saying we’re bound by our traditions. Stuck. Choiceless. They’re so ingrained in us, in our DNA, that, even in death, we are unable to escape their unyielding influence.

It would make sense then for the characters in Dance of the Dead to be annoying stereotypes as a way of reifying, “Hey, we’re forever confined by society’s expectations of us and there really is no way out.” And, yes, everyone in this movie is a stereotype, but they’re far from annoying. In fact, they’re comforting. You know these people. You’ve seen them on screen all your life. Each character is so painfully and authentically themselves that you feel like you’re collecting trading cards or something. And the whole thing makes you wish you could be that way. That you could know exactly what type of person you are and not be afraid to show it, ever.

Maybe that last part is just me. And they really are annoying, but it’s all on purpose so that when they each inevitably grow and change at the end of the movie, it’s more meaningful.

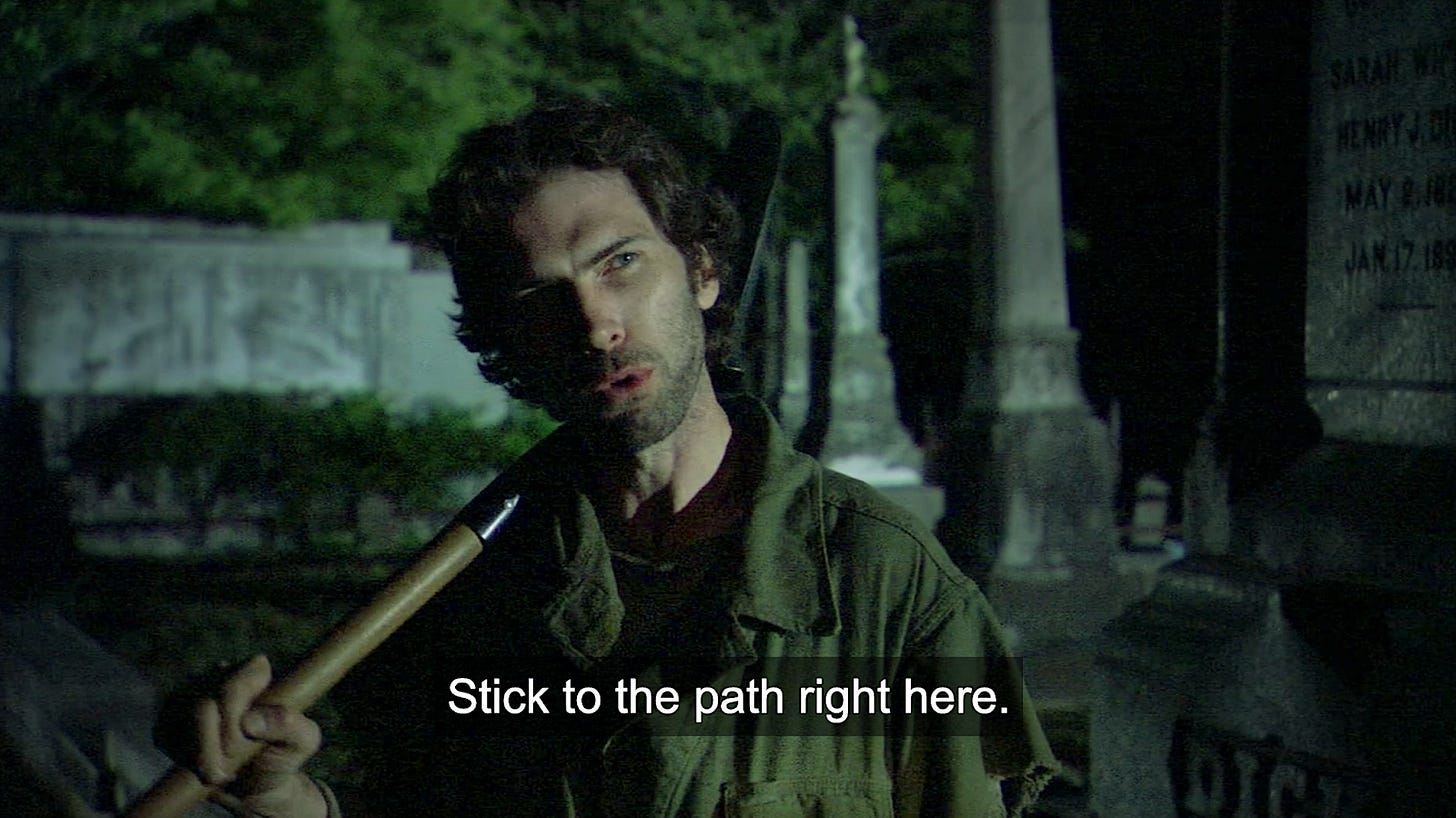

There’s this scene early on where the sci-fi club is walking in the cemetery looking for supernatural beings. The creepy graveyard groundskeeper pops out of nowhere to warn them to stay on the path and to not wander the grounds. It could just be a throw-away line9, but I don’t think it is. It’s ominous. It’s foreboding. It’s prophetic. It’s the world telling us to never deviate from the norm, because bad things will happen if we do. And as soon as the kids do stray from the path (enter a mausoleum), the dead literally shoot out from their graves.

So, in the end, when almost every character gets an arc and changes for the better, the movie proves the groundskeeper wrong: by leaving the path assigned to them, the characters can actually grow and change. The screw-up shows he’s not a screw-up. The nerd “gets the girl.”10 The bully turns out to be sensitive and vulnerable. Don’t get me wrong, they’re still themselves, but now with added layers. They have depth. In the last scene, the survivors blow up the school, demolishing not only the building but also the institution of prom itself and every single inane tradition that comes with it. I see it as a big middle finger to conformity. Like, the entire world is telling you to be this one type of thing, and you’re saying, “No, actually I don’t have to. I don’t have to ‘stick to the path’ because there is no fucking path.”

My favorite part is at the end. The school is burning to the ground in the background, and Jules, the president of the sci-fi club, turns to the prom queen who he has just rescued from the zombies. He congratulates her on winning. She says, “Like it matters.” She realizes everything she’s ever cared about, fitting in, winning, being pretty, all of that, doesn’t matter. And after years of being left out, bullied, and fully cognizant of society’s impossible expectations, Jules says, “Tell me about it.”

And now, they are equal. They are both aware that when all is said and done, the standards set by the masses are completely and totally meaningless.

In Otis, a horror comedy also from 2008, we see the catastrophic effects of what lifelong soul-crushing pressure to conform–and failure to do so–can do to a person.

And it can all be traced back to prom. Otis, a pathetic 40-year-old pizza delivery man, kidnaps 16-year-old blonde girls, chains them in his basement, and forces them to play out his high school fantasy. His goal is to take his victim to “prom,” something he touts as a night that will be “magical” (no doubt a remnant of what he’s been promised since he was a kid—a magical night, a perfect night, a night to remember). But when each girl fails to live up to that fantasy—and doesn’t even make it to the fake prom—he discards them and starts all over again.

The movie follows his latest victim, Riley, as she plays along in order to stay alive. Just like the girls before her, Riley is chained up in Otis’s basement, which is decorated to simulate a teenage girl’s bedroom: floral wallpaper, pink bedspread. He calls her on the telephone, he takes her on “dates,” he dresses her up as a cheerleader. He even calls up Riley’s parents to ask for permission to take her to “prom.” He does most of this from a control room of sorts, watching, through cameras, like a god.

And just like with the victims before, he forces Riley to go by the name “Kim” (the name of his brother’s wife and 20-year obsession). If Riley disobeys and says her name’s not Kim, he punishes her.

Otis forces Riley to “play along” with his fantasy, to give in.

But he’s literally mimicking the same words his abusive brother yells at him:

Except what his brother really means is, “Why can’t you just be normal?”

I think that Otis believes that what he’s doing will get him to normalcy. His MO is to run through this list of adolescent rites of passage, of teenage milestones, with the girls he kidnaps. First dates, phone calls, the “will you be my girlfriend” conversation. He’s doing what society expects of him (and what society promised him). Even down to gender roles. When he puts Riley in a cheerleading uniform, Otis wears a football jersey. When it’s finally time for faux prom, she wears a pink dress, Otis a blue suit.

There’s also a B-plot which involves Riley’s family planning to murder Otis after she escapes from his basement. Her mom is played by Ileana Douglas in an absolutely bonkers performance, her dad is Daniel Stern, and her little brother is played by Jared Kusnitz (see: future horny little brother LISTLESS).

Just wanted to shout out Jared Kusnitz because he’s in both Otis and Dance of the Dead. 2008 was Kusnitz’s year.

The last movie on this list is from 2009, and Jared Kusnitz is not in it. It’s also not a horror comedy in the same way the first two are. It’s much darker, more violent, and my favorite on this list. Sean Byrne’s The Loved Ones follows Brent, a dead-dad-greasy-hair-Metallica kid as he’s kidnapped and tortured by Lola, a girl at school whose invitation to the dance he turns down. He rejects her in a nice way though; he’s going with his girlfriend, and he apologizes twice. But that doesn’t matter. Lola’s going to have her own little prom, complete with her own little fucked-up traditions.

I’ve been obsessed with Lola ever since I first saw her on screen. She’s shy, quiet (at least at school), clearly an outcast. But Brent’s an outcast too, so maybe they’ll be friends. But, no, it’s one of those cases where she’s not the right kind of weird. She’s too weird (see: May).

Her dad’s really the one who kidnaps Brent. But he does it for Lola. They’re both in on it. And turns out, they’ve done it many, many times before. After Brent’s abduction, we get a glimpse into Lola’s life. The pop ballad “Not Pretty Enough” by Kasey Chambers plays on her pink CD player over closeups of her things—Barbies and baby dolls, magazine cutouts of headless male abs, a plastic tiara, lip gloss, and her scrapbook full of hand drawn white knights, castles, hearts and arrows. This girl was clearly promised a fairytale. Movies, books, magazines, her dad, etc. all fed her an idealized version of love, of a storybook romance, that real life could never possibly live up to.

Just like Dance of the Dead, The Loved Ones highlights the absurdity of tradition. Sure Lola and her dad do conventional stuff at their fucked-up prom (it’s technically the “end of school dance,” but for the sake of my list, it’s prom), like when Lola’s dad crowns her queen of the dance. But they’ve also got their own stuff going on. Like when they inject Brent’s throat with bleach, rendering him speechless, it’s clearly something they do every kidnapping. They even smile and chant together: “We can’t hear you!”

Later, it’s time for the lobotomy (boiling water poured into a drilled hole in the skull). The dad lets Lola drill the hole for the first time, guides her through it, like he’s teaching his daughter how to drive. Just another familial custom.

And like with Otis, The Loved Ones’s villain is forged by unattainable expectations, showing us how severe the consequences of societal conventions can be.

Both Lola and Otis were conditioned since birth to believe false notions of how life would be, so when they grow up and life doesn’t even come close, of course all hell breaks loose.

Lola represents everything I actively avoided all my life. She, no doubt, wore those DRAMA QUEEN ANGEL STAR PRINCESS SPOILED CUTIE t-shirts. And do you think she cared if anyone said anything to her about them? Well, she may have cared, but she probably would have just murdered them.

Look at her nails…her outfits, her room, her scrapbook. She loves pink glitter. If it was crazy sock day at her school, I think she would wear socks like mine.

I understand that after talking about all these movies that rip prom a new asshole, I may be coming off as bitter, prom-hating, and full of regret. And I truly thought that when I got older, I might actually have some FOMO about it. That I’d say, “Damn, if only I was allowed to truly be myself.” But, the thing is, not going to prom is me. “Nice socks” is me. Dressing normcore is me. And whether I like it or not, right now, I’m the most “me” I’ve ever been.

Unable to shoehorn my favorite trope into this, which is “Cool Real Band Plays at the Dance,” so here’s a footnote. Likely the first time I saw this happen was in Grease, with Sha na na as Johnny Casino and the Gamblers, but here are some other great ones with links for your viewing pleasure: The Offspring in Idle Hands, Good Charlotte in Not Another Teen Movie, Moonpools and Caterpillars in Wish Upon a Star (my favorite), even a Suicidal Tendencies offshoot in Encino Man, and the greatest and most obvious example, Save Ferris/Letters to Cleo in 10 Things I Hate About You.

Read wigwagmag.com!!!!!!!!

Preston (Ethan Embry) from Can’t Hardly Wait is the one that immediately comes to mind, but another I saw recently is Sean Astin’s character in Encino Man. Like, shut the fuck up! You have Brendan Fraser as a caveman, yes, but you also have the wonderful free spirit Pauly Shore right next to you teaching everyone to embrace their uniqueness/individuality, while also pretty much teaching us all a new language, and we’re supposed to pay attention to your piece of the plot?

Here’s another great use of “Come Sail Away” at a Homecoming Dance in something that came out in 1999 :)

A wonderful trope of longing; one of my recent favorites is from Love and Basketball

I watched the Stranger Things dance scene the same day I watched this, a total coincidence, and speaking of brutal rejections: Dustin! But there’s redemption when Nancy steps in to make all the mean girls jealous. A real Romy & Michelle meets Lindsay Weir moment…it’s even set to “Time After Time”

This one’s a little more complicated; the movie ends up confirming that the mean kids are “bad people with ugly hearts,” and even though Michele acknowledges her own role, saying, “I bet in high school, everybody made somebody's life hell,” what are we to make of Sandy Frink? Michele is terrible to him only until he becomes rich. Justin Theroux’s cowboy doesn’t get Heather Mooney (Janeane Garofalo) until he loses his stutter and gains the confidence to approach her. Heather only feels better once she learns she, too, made someone's life hell, Camryn Manheim’s Toby, but this realization of cruelty only makes her feel belonging, not regret. And what does Toby get out of any of it? Much to think about…

Fwiw my version would’ve come out in 2000 and starred Patrick Fugit as Charlie and Carly Pope as Sam

Also possibly a reference to An American Werewolf in London…

They both turn into zombies while making out and eat each other’s faces off, but my point still stands.

meted this out throughout the day like i was savoring the last piece of halloween candy. divine!!! May (movie) mentioned :):)